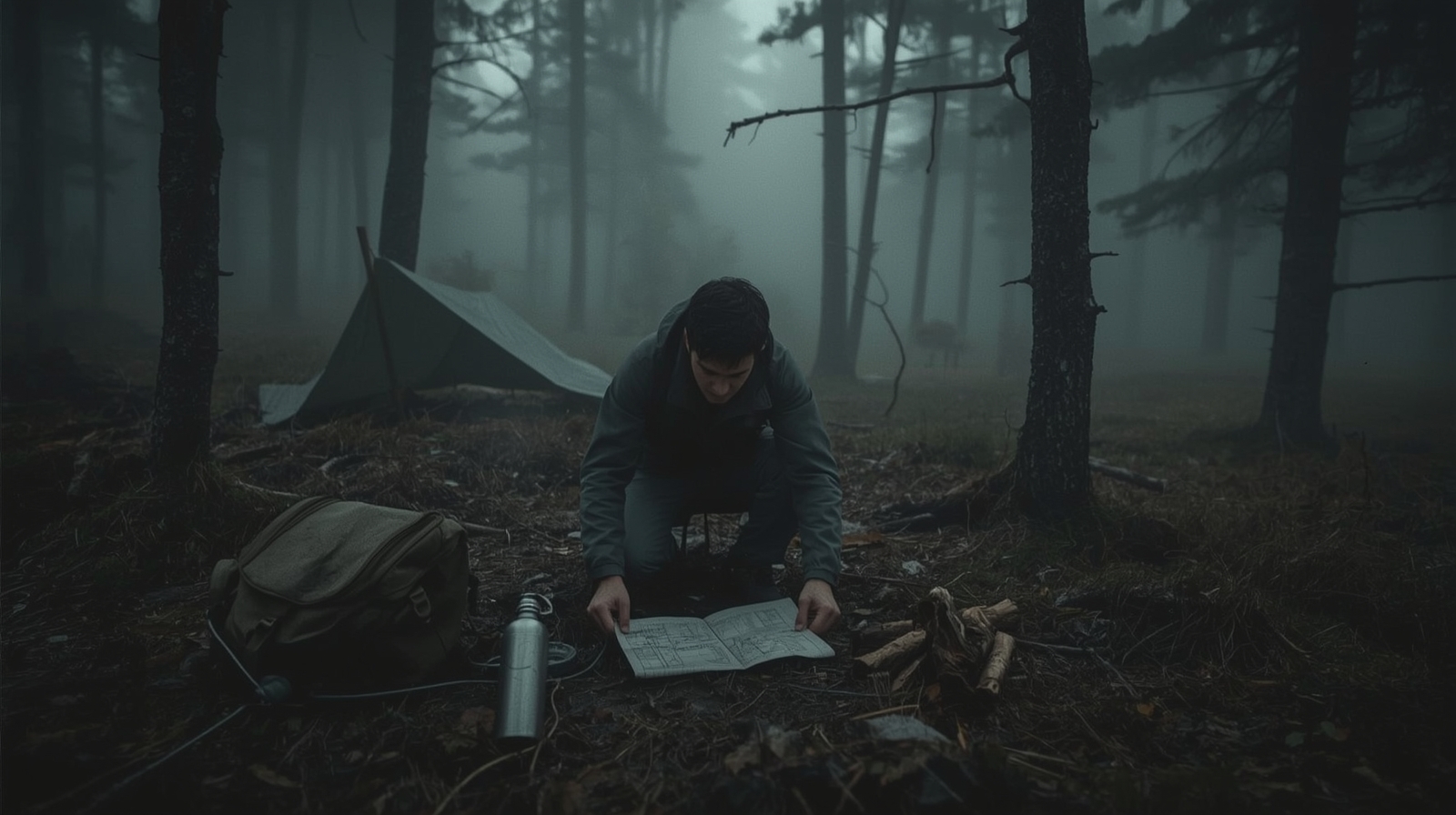

Lost in the Backcountry: The 60-Minute Self-Rescue Protocol (STOP, Signal, Shelter, Water) and the ‘Don’t Wander’ Rules

Operational Reality Check: Getting Lost Is a Cascade, Not a Single Mistake

When people get lost in the backcountry, it’s rarely because they’re incompetent. It’s usually a chain reaction: a small navigation error, a bad assumption, a time slip, a weather shift, then a decision made under stress. In the military we call that a cascade. The first error is survivable; the follow-on errors are what turn a hike into a rescue.

Your job in the first hour is to interrupt that cascade. Not with heroics. With discipline. If you do nothing else, you follow a simple protocol and you stop moving until you have a plan you can defend.

The 60-minute mission:

— STOP — freeze the spiral, stop all movement

— Anchor — mark location, assess injuries, establish your base

— Signal — make yourself findable while you still have energy and light

— Shelter — build before conditions force your hand

— Water — secure a treated source with minimal movement

The hard rule: don’t wander. Movement without a verified plan is how you widen the search area and burn your remaining daylight, calories, and morale.

The 60-Minute Self-Rescue Timeline: What “Good” Looks Like Under Stress

Time matters. Not because you’ll die in an hour, but because the first hour is when most people make the worst choices. The goal is to convert panic into a checklist-driven routine.

- Stop moving. Pack down.

- Nose in, mouth out. Slow it down.

- Inventory immediate threats: injury, wet, cold, darkness.

- Mark your location visibly.

- Check map, compass, GPS, offline maps.

- Decide posture: self-rescue or shelter-in-place?

- Activate PLB or satellite messenger if available.

- Whistle: 3 blasts, pause, repeat.

- Move to visible ground only if safe and close.

- Shelter first if cold, wet, or windy.

- Identify nearest water source on map.

- Treat, drink to function. Ration activity, not water.

STOP Protocol: The Discipline That Prevents the Death Spiral

STOP is simple, but it’s not easy. It’s a behavioral lock that prevents you from “just checking over the next ridge” until you’ve burned half your daylight and doubled the search area.

S — Stop: Lock down movement

Stopping feels wrong because your mind wants to “fix” the problem with motion. That urge is the enemy. If you’re lost, movement without verification is how you become more lost. Drop pack, sit, and physically commit to a pause. If you’re with a group, take control: one voice, one plan, no freelancing.

T — Think: Build a defensible picture

You’re trying to answer three questions: Where was I last certain? What changed? What is the safest next action?

- Last Known Point (LKP): the last place you could prove your location — trail junction, stream crossing, summit sign, distinctive landmark.

- Time and distance: how long since LKP, at what pace, and with what elevation change?

- Hazards: cliffs, river crossings, avalanche terrain, heat exposure, lightning risk.

O — Observe: Use your senses like instruments

Observation is not “looking around.” It’s collecting data. Wind direction, cloud build, temperature drop, animal trails, human noise, water sound, and terrain aspect all matter.

- Look behind you — many people miss obvious back-tracks because they only scan forward.

- Check the ground — your own prints, trail tread, cut logs, cairns.

- Check the sky — weather is a schedule you don’t control.

P — Plan: Decide a posture and commit

A plan is a decision with criteria. “I’ll keep walking until I find the trail” is not a plan — it’s a hope. A real plan sounds like: “I will shelter in place, signal every 15 minutes, and conserve battery. If no contact by dark, I bivy here.”

One sentence test: If you can’t describe your plan in one sentence with a trigger and a limit — time, distance, or daylight — you don’t have a plan. You have anxiety dressed up as action. Write it down or say it out loud to your group before you move.

The ‘Don’t Wander’ Rules: Movement Is a Tool, Not a Reflex

Most backcountry fatalities tied to being lost involve one of two failures: exposure (cold/wet/wind) or injury (falls, bad crossings, exhaustion). Wandering increases both. These rules are blunt because the environment is blunt.

“I’ll just go check” is a common last sentence before a missing-person case opens. Solo scouting without comms, without a visible line back, and without a time limit turns one problem into two. If you leave the anchor point alone, you are now the problem.

Signal Like You Mean It: Make Rescue Easy, Not Heroic

Signaling is not an afterthought. It’s an early action — because you have more light, more energy, and more options before night and weather tighten the vise. Your objective is to be seen, heard, and located.

Priority order: PLB/Satellite first, then phone, then analog

Whistle procedure: standardized and repeatable

Use the international distress pattern: three blasts, pause, repeat. Don’t scream — screaming burns hydration and voice strength. A whistle carries farther and keeps your airway intact.

- 3 blasts (1–2 seconds each), strong and deliberate.

- Wait 30–60 seconds and listen for a response.

- Repeat for 5 minutes, then rest for 10 minutes.

- Resume the pattern every 15 minutes — adjust for energy and conditions.

Visual signaling: contrast and pattern beat brightness

Rescuers scan for unnatural shapes and colors. A bright jacket laid flat, an X made from branches, or reflective material flashed in a pattern works better than random waving.

- Signal mirror: aim using the “V” method with your fingers; sweep slowly across likely aircraft approach paths.

- Headlamp: three flashes, pause, repeat. At night, light is king.

- Ground-to-air symbols: X = need help; arrow = direction of travel (only use if you are moving with a confirmed plan).

Pick a signal site that’s safe to hold for hours. Open meadow, ridge shoulder, lakeshore — good. Lightning exposure, cliff edges, avalanche path — you’ve traded one emergency for another. Line-of-sight matters, but survivability at that spot matters more.

Shelter First When Exposure Is the Threat: Fast Builds That Work

In many temperate and mountain environments, exposure is the real clock. Hypothermia can occur well above freezing, especially with wind and wet clothing. Shelter is not a comfort item — it’s a heat-management system. Build it before you need it, not after you’re already shivering.

Shelter site selection: avoid the three killers

- Wind: get leeward of terrain features, not under dead branches or widowmakers.

- Water: avoid dry creek beds and low spots that can flood — they fill fast and silently at night.

- Falling hazards: dead branches, unstable rocks, steep snow slopes above your site.

The 10-minute shelter hierarchy — best available, fastest safe

Ground insulation: the part people skip, then shiver all night

Cold ground will steal heat faster than cold air. If you have a pad, use it. If you don’t, build a mattress: dry leaves, pine needles, grass, spare clothing, your empty pack under your torso. You are creating an insulation barrier, not a bed. At least four inches of compressible material between you and the ground.

Clothing discipline: if you’re sweating, you’re losing. Sweat becomes cold later — often exactly when you need it least. Vent early, slow down, and change into dry layers if you have them. Keep one dry layer protected in your pack for sleep if conditions allow. Do not put on that layer while you’re still moving.

Water Without Self-Sabotage: Hydration, Treatment, and Rationing

Thirst makes people move when they shouldn’t. But drinking untreated water can turn a survivable situation into a medical problem that unfolds over the next 48 hours. Your objective is to secure water with minimal movement and minimal risk.

Find water with a map-first mindset

- Check your map for streams, lakes, and springs near your anchor point before you walk toward water.

- Listen — moving water is often audible before visible. Don’t chase a sound you can’t confirm on the map.

- Don’t chase water into steep drainages late in the day. The descent cost is high and the return is worse.

Treatment methods — pick the one you can execute correctly under stress

| Method | Speed | Reliability | Watch Out For |

|---|---|---|---|

| Filter | Fast | Protozoa + bacteria | Protect from freezing — a frozen filter membrane fails silently |

| Chemical tablets | 30–60 min contact time | Good for most sources | Less effective in very cold or turbid water — double dose if murky |

| Boil | Slow | Highly effective | Costs time, fuel, and a container — but works when filters freeze |

For authoritative guidance, the CDC’s backcountry water treatment recommendations are the field standard.

Ration activity, not water. In most environments, you don’t save water by refusing to drink — you save water by reducing exertion, staying shaded, and avoiding panic movement. Drink to maintain function. Dehydration impairs judgment, and judgment is your primary survival tool.

Don’t eat snow raw. Eating snow drops your core temperature and costs calories — a double penalty when you’re already cold. Melt it if you can. If you must eat snow, take small amounts and warm it in your mouth slowly, and understand you are trading heat for hydration.

Navigation Triage: How to Rebuild Your Location from First Principles

Once you’ve stabilized with STOP and addressed immediate exposure risk, you can attempt to re-establish your position. This is not about proving you’re tough — it’s about being precise. A wrong position fix is worse than no position fix.

Reconstruct from the Last Known Point (LKP)

- Identify the LKP on your map — the last place you could confirm your location with certainty.

- Estimate your travel since then: time elapsed, pace estimate, and elevation gain or loss.

- Compare terrain features: ridges, drainages, aspect, major stream bends. Match what’s on the map to what you can see.

Use handrails and backstops like a professional

A handrail guides you along a feature. A backstop prevents you from overshooting your target. Example: “Follow the creek downstream until it hits the main river (backstop), then turn left to the bridge.” If you don’t have a backstop defined before you move, you’re relying on luck to know when to stop.

Compass basics that prevent big errors

- Orient the map. Map north to magnetic north — account for declination if you know it.

- Confirm major terrain. If the map shows a ridgeline east and you see it west, you’re reversed. Stop and fix it before moving.

- Avoid single-point certainty. One landmark can deceive you. Confirm with two or three independent features.

Phone GPS battery discipline: Use it deliberately. Brightness down, airplane mode on, short checks — then off. Take screenshots of your location and offline map tiles if you have service. Don’t stream maps when you’re already in trouble. Every percent of battery is worth protecting.

The National Park Service’s hiking safety guidance covers navigation triage and what to do when lost — worth reading before your next trip out.

Medical and Exposure Priorities: Treat the Real Emergency First

Being lost is not automatically deadly. Exposure and injury are. If you’re bleeding, hypothermic, or heat-stressed, navigation becomes secondary. Stabilize the casualty first.

Hypothermia: the slow, quiet performance killer

Early signs include uncontrolled shivering, clumsiness, and poor decision-making. The insidious part: mild hypothermia impairs judgment before you know it’s happening.

- Get out of wind and wet conditions immediately.

- Add dry layers — protect head, hands, and neck first.

- Eat calorie-dense food and drink warm fluids if available.

- Shelter from wind even if temperature feels manageable — wind chill drives heat loss faster than most people expect.

Heat illness: when “just keep walking” becomes a medical problem

Heat exhaustion and heat stroke develop when you push in the sun with low water. Shade, cooling, and reduced movement are the immediate actions — not finding the trail.

- Get to shade and loosen clothing.

- Cool the body: wet cloth on neck, armpits, and groin if water allows.

- Do not force-march to “find the trail” — that’s how you collapse away from help.

Lower limb injuries: the common trip-ending failure

An ankle sprain in steep terrain is often the moment self-rescue ends and signal-and-wait begins. Stabilize the joint, reduce swelling with elevation if possible, and shift posture to signaling and shelter. Moving on a bad ankle multiplies injury and can turn a walkout into a litter carry.

Decision Point: When to Self-Rescue vs. Shelter-in-Place

Self-rescue is not always wrong. But it must be justified. The backcountry punishes optimism.

| Factor | Move Is Possible | Hold Position |

|---|---|---|

| Injury | No injury, stable footing | Sprain, pain, limp, dizziness |

| Weather | Stable, warm, low wind | Rain, wind, cold, lightning |

| Navigation certainty | Confirmed location + route | Guessing or conflicting cues |

| Daylight | Hours remaining | Dusk or night approaching |

| Terrain | Known trail or road ahead | Cliffs, drainages, thick brush |

Self-rescue requires ALL of these to be true simultaneously:

— You can positively identify your location on the map (not “pretty sure”)

— You have a known route to a known point — trailhead, road, staffed facility

— Terrain between you and that point is within your ability and daylight window

— You can move without triggering exposure risk: sweat → cold soak, heat stress

If any one of these is missing — hold position and signal.

Night Operations: How to Survive the Dark Without Making It Worse

Night changes the rules. Visibility collapses, temperature drops, and navigation errors spike. Unless you have a verified route on a known trail with adequate light and energy, night is when you hold position.

Light discipline: preserve power and preserve options

- Use the lowest headlamp setting that still works for your task.

- Keep batteries warm — inside a jacket pocket in cold environments. Cold batteries lose 30–50% capacity.

- Treat your phone like a field radio: short deliberate use, then off. Every percent matters.

Fire: useful tool, high liability

Fire can provide warmth and signaling, but it’s not mandatory and it’s not always smart. In dry or windy conditions, fire can escalate into a wildfire — which becomes criminal, catastrophic, and immediately life-threatening.

- Only build a fire if conditions are safe, legal, and you can control it.

- Clear to mineral soil, keep it small, and have an extinguishing plan ready before you light it.

- If you can’t guarantee control, skip it and focus on shelter and insulation instead.

The dark amplifies normal forest sounds. Don’t interpret every noise as a threat. Your job at night is to maintain shelter, keep warm, and continue a signaling rhythm. Panic burns calories and leads to the kind of dumb decisions that open second rescue cases.

Common Failure Patterns — and How You Prevent Them

These are repeat offenders in real incidents. Learn them now so you don’t live them later.

Field Checklists: What to Do, What to Say, What to Track

The 60-minute checklist

- STOP — Stop moving, breathe deliberately, stabilize.

- Anchor — Mark location visibly. Note time. Assess injuries.

- Signal — PLB or satellite messenger if available. Then whistle/visual pattern.

- Shelter — Wind protection first. Ground insulation second. Dry layers third.

- Water — Locate nearest source on map. Treat it. Drink to function.

- Plan — Decide hold vs. move with explicit criteria and hard limits. Say it out loud.

If you reach 911 or a ranger: a clean report template

Keep it short and factual. Dispatchers need specific information fast — give it to them in this order.

For additional decision-making and preparedness frameworks, FEMA’s Ready.gov provides standardized guidance applicable to backcountry self-rescue situations.

- ACR ResQLink 400

- McMurdo Fast Find 220

- Ocean Signal PLB1

- Garmin inReach Mini 2

- SPOT Gen4

- Zoleo Satellite Comm.

- Fox 40 Classic

- UST JetScream

- Acme Tornado 2000

- StarFlash 2×3 in.

- Coghlan’s signal mirror

- UST StarFlash Pro

- SOL Escape Lite Bivy

- Tact Bivvy 2.0

- Go Time Gear Life Tent

- Sawyer Squeeze

- Katadyn BeFree 1.0L

- Platypus QuickDraw

- Suunto A-10

- Silva Ranger 2.0

- Brunton TruArc 5

- Adventure Medical Kits

- MyMedic MyFAK

- NAR SOFTT-W tourniquet